|

Sharkfest.com IS DEVELOPING A CURRICULUM PROCESS FOR A FOUNDATION IN THE SCIENCES WITH EMPHASIS ON TECHNICAL ANALYSIS. OUR "FURTHERING EDUCATON PROGRAM" COORDINATES WITH OUR SITES IN CENTRAL AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN REGIONS. (NOVEMBER 2004 STREAMING BROADBAND CURRICULUM PROGRAMS FOR PRE K-9 CLASSES) WHICH WILL BE PRODUCED FROM THE FLORIDA KEYS.

THE CURRICULUM WILL BE ON A SUBSCRIPTION BASIS AND WILL ALSO BE INTERACTIVE "LIVE" WITH OUR SCIENTISTS SUPPLEMENTING THE EFFORTS OF THE TEACHER THUS DELIVERING AN INTRIGUING PROCESS THAT WILL STIMULATE THE STUDENT'S ABILITY TO UNDERSTAND THE FRAGILITY OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT. THE DELIVERY METHOD WILL BE IN REAL-TIME AND WILL ALSO BE AVAILABLE ON CD-ROM OVERNIGHT MAILED TO THE CLASSROOM AS TO CONTINUE THE FLOW OF EXCITEMENT.

THROUGH OUR SPONSORS WE WILL BE OFFERING AWARDS TO STUDENTS THAT FULFILL CERTAIN CURRICULUM GOALS AND THESE AWARDS WILL BE GIVEN OUT ON A WEEKLY BASIS BY OVERNIGHT DELIVERY.

OUR CELEBRATIONS THAT HAVE HONORED THE MARINE ENVIRONS AND THE SPECIES SINCE 1939 WILL BE SCHEDULED FOR THE JANUARY - MARCH SEASON... AS HAS BEEN DONE FOR OVER 50 YEARS.

mail to: SHARKFEST.COM / P.O. Box 1119, Key West, Florida 33041-1119

Site Copyright 2021 & Trademark of Key West Institute. by Key West Register Corp. / sharkfest.com and Sharkfest TM (since 1939) are part of the Key West Register Corp.

On the other hand, people eat tons of shark meat annually,said an assistant fish curator at SeaWorld. "

______________________________________________________________

Key West Institute Commemorative Medallion "Caring for Sustainable Resources"

Medallion created by Internationally awarded Wildlife Artist Mr. D. Cusenza of the Pacific Northwest

Medallion $99.95 postage paid Florida Residents add sales tax

|

PILOT WHALE PRIMER:Adult short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) range from about 13 to 18 feet long (4 to 5.4 meters), with black/grey bodies and bulbous heads. Mass stranding of this species is not uncommon.

When two or more whales strand it is called a mass stranding. Researchers do not have a single, definitive reason why these animals strand, but there are many theories. The social nature of the animals, stormy weather, extreme tides, and offshore animals following prey inshore are some of the most likely causes. (The main food of pilot whales is squid, which come inshore to spawn.) Some other identified causes of stranding are disease, parasite infestation, harmful algal blooms, injuries due to ship strikes or fishery entanglements, pollution exposure, trauma, and starvation. In addition, strandings often occur after unusual weather or oceanographic events. In recent years, high concentrations of potentially toxic substances in marine mammals and an increase in new diseases have been documented, and scientists have begun to consider the possibility of a link between these toxic substances and marine mammal mortality events. Pilot whales are extremely social animals that typically stay in very tight groups. Older, more experienced animals who are familiar with feeding areas and migratory routes may act as leaders. (It is for this reason that they are called pilot whales.) If the leaders become sick or disoriented, or follow prey too close to land, they may come ashore, causing the rest of the group to follow.

Family Lamnidae

Common names: White shark (USA), white pointer, white death (Aus.), blue pointer, Tommy shark, Uptail (S. Africa).

French: Grand requin blanc; requin blanc; Lamie (Nice)

Spanish: Tiburón blanco; jaquetón blanco; Tauró blanc (Catalunya); salroig (Majorca); Marraco (Barcelona); Sarda (Canaries)

Italian: Squalo bianco; pescecane; mangia alice; damiano (Naples); tunnu palamitu di funnu (Catania); pici bistinu (Messina)

Croatia: Pas ljudozder

Portuguese: Tubarão

German: Menschenhai

Maltese: Kelb il-bahar; Kelb-il-bahar abjad; Silfjun; Huta tax-xmara

Afrikaans: Witdoodshaai

• History

The great white shark, within the monotypic genus Carcharodon, is related to four other Mackerel sharks (Makos, Isurus spp. & Porbeagles or Salmon sharks, Lamna spp.) in the Family Lamnidae.

Only one white shark species recognised by taxonomists - but it was not always known as Carcharodon carcharias, the 'Jagged-Toothed One'. Carolus Linnaeus, in his 1758 tome Systema Naturae, named it Squalus carcharias and thereafter the species was afforded a variety of binomials, including Carcharias lamia, Carcharias verus, Carcharodon smithii and Carcharodon rondeletii.

This shark was known from the Mediterranean in ancient times, most probably being the fish referred to by Aristotle and other Greek writers as the fearsome Lamia monster - a common-name still used for this species both in Greece and in places along the coast of southern France (where it is called the 'Lamie'). They were not uncommonly caught between Sète and Nice in medieaval centuries, and specimens were of as much interest to the writers of the time as they are today. In 1566, the Montpellier-based naturalist Guillaume Rondelet noted the voracious appetite of the Lamia ; a diet which, he commented, included tuna and even the odd human - and suggested it was this animal, rather than a whale, that was responsible for swallowing the prophet Jonah in the famous biblical fable. It's not hard to see where Rondelet's reasoning originated. The white shark was then - as it is now - a little-known, rarely seen but greatly feared animal of mythical status, whose apparent penchant for consuming humans (in a mystical sense!) was well-known amongst the region's seafarers. It seems quite conceivable that, on some ancient shoreline and unrecorded date, a white shark was caught and eviscerated, leading to the rare discovery of human remains, perhaps largely intact and fresh, in its stomach (e.g., see Conorelli & Perrando, 1909, for a genuine example of this). Such an event would unquetionably spark considerable public interest and quickly evolve into local fable. Perhaps inserting the 'whale' element gave the story a more benign feel, as befitting the religious context into which it is now told.

Throughout much of the 18th and 19th Century, there was confusion in the proper identity of the white shark amongst the Mediterranean elasmobranch fauna. Its triangular, serrated teeth proved a cornerstone in fuelling the nomenclaturial and descriptive mayhem that followed - not least as a much more common Mediterranean species, the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus, has teeth that may - at least when compared solely by cursory, written description - fit adequately into the white shark 'mould'. The thought of the essentially inoffensive sandbar shark being unwittingly catapulted to 'maneater' status may seem amusing in hindsight but, at the time, such fundamental errors of identification generated many misrepresentative species accounts. The white shark was often grouped collectively with carcharhinids on account of their rather similar dentition. Poor illustrations of the white shark also abounded, exasperating the problem. The simple fact was that very few scientists describing this animal had actually seen one, either dead or alive, and much of the topical knowledge explicating both its physical appearance and behaviour drew more upon hearsay and mariner's lore than biological fact.

Marcus Bloch's (1785-95) illustration of Squalus carcharias is a typical case-in-point. The excised jaws are depicted upside-down - a fundamental mistake later to be followed blindly by other authors - and the shark itself bears only a limited resemblance to the fish we call Carcharodon carcharias. With an asymmetrical tail, small gill-slits and sail-like first dorsal fin, it might come as no surprise that the drawing has more than a passing similarity to Carcharhinus plumbeus. Arguably, it is only the single tooth, illustrated alongside, that can be readily attributed to the white shark. Meanwhile, Bloch's white shark "mugshot" doubtlessly condemned yet more benign sandbars to the maneater's Hall of Fame. It is poignant to add that a much earlier depiction, prepared by Guillaume Rondelet in 1554, was far more accurate than many later images - correctly showing a crescentic caudal fin and caudal keels. Even the relative positions of second dorsal and anal fins are precise.

Similarly, C.L. Bonaparte (1832-1841) illustrated the white shark in his description of Italian vertebrate fauna. His rendition is essentially accurate and almost certainly based upon a freshly-caught specimen. Interestingly, the black axillar blotch so often found on these sharks is missing from the picture - and indeed is often absent on many Mediterranean examples.

In 1838 L. Agassiz, a paleontologist, published a description of the genus now called Carcharodon with some precision in a catalogue of fossil fish, naming the living species as Carcharodon smithii. He had adopted the new generic name following the British naturalist and physician Dr. Andrew Smith who had, at some time whilst resident in South Africa between 1820 and 1836, procured a small white shark specimen from the Cape Province region. Smith was the first scientist to properly distinguish the genus and proposed the generic name Carcharodon in an 1838 work by the German anatomists, Johannes Müller and Fredrich Henle. In an 1839 discussion of white sharks, Müller and Henle again followed Smith's generic name and called the fish Carcharodon rondeleti. They suggested that the South African shark was somewhat different from other white sharks and might thus represent a second species.

As it happened, Andrew Smith was to personally describe his specimen in a later publication of 1849, naming it as Carcharodon capensis in reference to its capture-locality. He mentioned stomach-contents and noted aspects of white shark behaviour with an air of reality far divorced from the mediaeval-inspired writings and mythos that existed before. In 1851, J.E. Gray synonymised Smith's animal with C. rondeleti, realising that this was one and the same species, rather than a unique South African endemic. This assertion has been followed ever since.

For decades, Smith's stuffed C. capensis holotype - a juvenile female measuring just over 2 metres in length - lay gathering dust and more than a few errant white paint-splashes in the storage basement hall of the British Museum of Natural History, London - until re-discovered there in June 1994 by Leonard Compagno, Oliver Crimmen (of the museum's Fish Section) and the author. Manoeuvring the hefty specimen down from it's ceiling-high resting place on a top shelf, and then lifting it up two flights of stairs to a laboratory, was an exhausting episode taking perhaps more physical effort than the process of actually catching it in the first place. Despite showing its age, the shark still had a legible pencilled label affixed to its wooden base, reading "Carcharodon capensis, Cape Seas". Preservation was sufficiently good to even see the black axillar blotch beneath each pectoral fin insertion. The anal fin, however, was missing - perhaps accidentally destroyed during the mounting process.

Arguably equalled only by the killer whale (Orcinus orca) as a marine macropredator, the great white shark occupies a cosmopolitan range throughout temperate seas and oceans and will occasionally penetrate tropical zones. Principally an epipelagic dweller of neritic waters, Carcharodon is found from the surfline to well offshore, at the surface and to depths over 250m on the bottom; commonly patrolling small coastal archipelagos inhabited by pinnipeds , rocky headlands where deepwater lies close to shore and offshore fish reefs, banks and shoals.

Description hortfin mako.

A fusiform, heavy-bodied shark with a crescentic caudal fin and large, triangular, coarsely serrated teeth. In juveniles under 1.8 m, the teeth have small lateral cusplets and in neonates, anterior lower-jaw teeth may essentially lack marginal serrations. Typical tooth-count is:-13 / 11-12

The snout is conical, blunt and dorsally flattened; the five gill-slits are large but not encircling the head. The first dorsal fin, nearly an equilateral triangle in shape with a slightly concave rear margin, has its origin opposite, or slightly anterior, to the inner corner of the pectoral fins. The first dorsal is rounded at the apex in neonates but becomes more acutely-pointed within the first two years. The second dorsal fin is minute and pivotable, its posterior margin above or slightly ahead of the origin of the equally diminutive anal fin. The broad, dorsoventrally depressed caudal peduncle is expanded laterally to form a prominent keel on either side, but without secondary keels on the ventral caudal lobe itself (as in the porbeagle Lamna nasus). The lunate caudal fin tends to have acutely-pointed tips in sharks over 2.0 m TL. In neonates, the lower (ventral) caudal surfaces may be more rounded and compressed but rapidly expand soon after birth. The caudal lobes are almost of equal size, with the lower (ventral) anterior margin measuring 76-92% of the same measurement on the upper (dorsal) lobe. The pectoral fins are large and moderately falcate.

• Color

White sharks vary from almost black to slaty-grey or dun above, with the ventral surfaces predominantly white. A strong, variable line of demarcation separates the dorsal and ventral surfaces with associated blotching, particularly near the gill-slits and above the pelvic fin bases. Small, irregular dark spots may be present on the flanks posterior to the 5th gill slit and the lateral surfaces have a bronzy sheen that may be structural and manifested only in strong sunlight. The ventral tips of the pectorals are black and most specimens exhibit a black oval blotch in the axil of the pectoral fin. The pelvic fins may be blotched with olive or grey; likewise the ventral caudal lobe, with white marks and white anterior booting. The mode of these demarcations vary greatly individually, but may exhibit common trends amongst sharks in a given geographical remit. The variance in dorsal pigment and tone is also very variable, especially between centers of abundance but also within them. Californian examples are often very dark slate-grey above, almost black. South African examples (Cape Province) tend to be somewhat more dun or olive, as do Australian specimens (but with much variance). Mediterranean specimens are predominantly slate-grey or dark olive-brown dorsally.

Size and Reproduction

The maximum size attained by white sharks remains a matter embroiled by debate and spurious information. Adult females can reputedly attain 7 metres based on an unconfirmed specimen from Kangaroo Island, Australia, taken in 1987. A further female taken off Filfla, Malta, in the same year was reported as 713cm TL by local sources but can be demonstrated, on the basis of a previously unexamined photo scrutinised in October 1998, to be considerably smaller at circa 530cm TL. It is realistic to suggest that maximum length of this species actually lies in the range of 550 to 600 cm TL. The smallest free-swimming examples, on the other hand, appear to be ca. 120cm TL.

Lengths at maturity for both sexes remain somewhat undetermined, and based on (currently limited) age-growth data it may be possible that different populations mature at varying lengths. The majority of females mature at between 450-500cm TL (Francis, 1996), but have been reported as immature at sizes as much as 472cm (Springer, 1939). Males mature at about 350-360cm (Pratt, 1996). A single study of age and growth, pooled from 21 specimens (Cailliet et al., 1985) suggests a generalised age of maturity of 10-12 years. A mature female of 500cm is estimated to have reached ca. 14 to 16 years.

• Weight-at-Length relationship

A recent allometric (size-on-size) equation for weight (W) versus total length (TL) is given by Henry Mollet and Gregor Cailliet (1996):

In W= 2.0686 + 3.0958 In TL (W in kg, TL in m)

y on x regression: In W= 2.1154 + 3.0542 In TL (N = 327; r2 = 0.973)

A further WT-TL regression was given by Compagno (1984), based on 98 specimens (mainly from California, with a range of 127 to 554cm):

WT = 4.34 x 10-6 TL 3.14

Distribution

White sharks occupy a cosmopolitan distribution throughout temperate seas and oceans and will occasionally penetrate tropical zones. Sporadically, they make incursions to cold, boreal waters and have been recorded from off the south Alaskan and Canadian coasts (Gulf of St. Lawrence). Principally an epipelagic dweller in neritic waters, the white shark is found from the surfline to well offshore, often in association with isolated islets and archipelagos inhabited by pinnipeds (e.g., the Farallon Islands, Marin Co., California; Neptune Islands and Dangerous Reef, Spencer Gulf, South Australia; Dyer, Seal and Bird Islands, South Africa), rocky headlands where deepwater lies close to shore (California and Oregon coasts; Central Chile; Ligurian Sea, Italy), or near offshore fish reefs and shoals (e.g., Adventure Bank, Sicilian Channel; Struis Bay area, Cape Agulhas, South Africa).

A synopsis of confirmed worldwide occurrences are listed below by geographic region. Indices of relative abundance (based on capture-records, sightings, interactions with man) are abbreviated thus: CA: Center of Abundance F: Frequent; O: Occasional; I: Infrequent; R: Rare; VR: Very Rare. Further remarks are added where relevant.

Northwest Atlantic and Caribbean:- Gulf of St Lawrence, Newfoundland, St. Pierre Bank, Sable Island, Bay of Fundy (O-R); New Brunswick, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Martha's Vineyard, Long Island, New York coastline and offshore, particularly within the 30-fathom contour (CA; F); south along US coast through the Carolinas to Florida (R-O). Gulf of Mexico, principally western Florida shores (I) but ranging past the Mississippi Delta to at least Corpus Christie, Texas (R); Caribbean occurrences - Florida Keys, Cuba (Cojimar), Bahamas (R).

Literature: Pratt and Casey (1985); Bigelow and Schroeder (1948); Schroeder (1938, 1939); Springer (1939); Piers (1934); Scattergood (1962); Scud (1962); Day and Fisher (1954); Templeman (1963); Guitart and Milera (1974).

Southwest Atlantic:- Central and Southern Brazil (R-VR), 10 examples known to 1993 of which 6 were from Rio de Janeiro State, 3 from Ceará State and 1 from Espírito Santo State; Argentinean coast at Puerto Quequén (Necochea) and south to at least C. Blanco (R).

Literature: Siccardi et al. (1981); Gadig and Rosa (1996); Gadig, pers. comm.

Northeast Atlantic:- Charente-Maritime coast of France (La Rochelle and Pertuis d'Aintoche; VR), north to the mouth of the Loire (VR, 1 old record); Gulf of Gascogne, Northern Spanish and Portuguese coast southwards to Tarifa and Gibraltar (VR). Azores Archipelago (I); Madeira (VR). Morocco, Mauritania, to Senegambia (Dakar region at Île de Gorée and environs), Ghana and Cape Verde Is. (R). Canary Islands at Gran Canaria and Tenerife (VR?); probably Lanzarote. Possibly Zaire but literature confusion likely with bull sharks, Carcharhinus leucas.

Literature: Quéro et al. (1978); Cadenat and Blache

|

Southwest Atlantic:- Central and Southern Brazil (R-VR), 10 examples known to 1993 of which 6 were from Rio de Janeiro State, 3 from Ceará State and 1 from Espírito Santo State; Argentinean coast at Puerto Quequén (Necochea) and south to at least C. Blanco (R).

Literature: Siccardi et al. (1981); Gadig and Rosa (1996); Gadig, pers. comm.

Northeast Atlantic:- Charente-Maritime coast of France (La Rochelle and Pertuis d'Aintoche; VR), north to the mouth of the Loire (VR, 1 old record); Gulf of Gascogne, Northern Spanish and Portuguese coast southwards to Tarifa and Gibraltar (VR). Azores Archipelago (I); Madeira (VR). Morocco, Mauritania, to Senegambia (Dakar region at Île de Gorée and environs), Ghana and Cape Verde Is. (R). Canary Islands at Gran Canaria and Tenerife (VR?); probably Lanzarote. Possibly Zaire but literature confusion likely with bull sharks, Carcharhinus leucas.

Literature: Quéro et al. (1978); Cadenat and Blache (1981); Fergusson (1996); Ellis and McCosker (1991, for Azores).

Mediterranean Sea (CA): Spain and Balearics, including Catalon Sea at Valencia, Vinaroz and Islas Columbretes; also recently (1992) from Tossa de Mar and Andraitx, Majorca; Cabo Salinas, Majorca; Menorca (R). Gulf of Lyons, particularly Sète, Palavas and Grau-du-Rois (I-O); Riviera and Côte D'Azur (I), Ligurian Sea, especially from Camogli and Portofino to La Spezia (O-R). Western Italy (Tyrrhenian Sea: Elba, Anzio, San Felice Circeo, Ponza, Lipari Islands, Naples, Calabria Region), Corsica, Sardinia, especially northern part at Capo Testa; southwest region at Isola di San Pietro (O); Morocco and Melilla (O); Algerian coast (I-O?), Tunisia, principally La Galite Islands, Cape Bon area and Gulf of Gabès near Kerkennah Islands and Djerba (O), Sicily (cosmopolitan, especially Egadi Islands, Trapani Region and Messina); Sicilian Channel, Pantelleria, Isole Pelagie and offshore banks (F-O); Malta and Gozo (I). Ionian Sea off Calabria (Capo Spartivento) and Galipolli. Southern and Central Adriatic off Puglia, Manfredonia, Ancona and Termoli; also Dalmatian coast near Split (I-O), Northern Adriatic, principally Istria and Kvarner Gulf of Croatia (I, formerly F), sporadically at Riccione, Rimini and in the Gulfs of Venice and Trieste. Corfu, Greek Mainland, Aegean Sea (Thermaikos Gulf, Thassos, Kavalla, Alexandroupolis) through Turkish coast (Foça region) to Bosphorus (R) but not Black Sea. Cyprus (O), Israel ('Akko) and Egypt (Agamy, near Alexandria) (R).

Literature: Doderlein (1881); Lozano Rey (1928); Tortonese (1956); Postel (1958); Bini (1960); Capapé et al. (1976); Fergusson (1995, 1996); Mojetta et al. (in press). See Bibliography for detailed listing.

Southeast Atlantic:- Gough Island (single recent record). Namibia, from Cape Cross and Swakopmund southwards (O, but little data) possibly north to mid-Angola?, entire Cape Province, especially eastwards of the Cape of Good Hope in False Bay, Walker Bay, Gansbaai, Danger Point, Kleinbaai, Dyer Island group (CA; F), Cape Agulhas region (Struisbaai, Die Mond, Arniston) and entire Wild Coast (F) to Port Elizabeth; Algoa Bay (especially Bird Island) to Natal (F); northerly extent of range along the Indian Ocean coast of Africa uncertain.

Literature: Bass et al. (1975); Cliff et al. (1989); Compagno (1991 and pers. comm); Compagno and Fergusson (1994); Levine (1996); Smith (1951).

Indian Ocean:- Northern Natal coast (F) but more sporadic towards tropical extremes, perhaps more extensive around Southern Mozambique and Madagascar than previously supposed, based on recent sightings. Kenyan coast at Malindi; limits to northerly range in Western Indian Ocean currently unclear. Appears absent in the Red Sea (one old, doubtful record) or a very occasional outlier at best. Kuwait coast and Persian Gulf (VR); Seychelles Island (VR), Cargados archipelago (VR); Sri Lanka (VR).

Literature: Cliff et al. (1989); Khalaf (1987); L.J.V. Compagno (pers. comm.); R.V. Salm (pers. comm.).

Indo-Pacific and Western Pacific:- Kamchatka region (VR, possibly dubious), Japanese Islands (Honsu and Hokkaido, including Inland Sea) (CA; O); Okinawa (I), Eastern Chinese Coast (VR), Korean Peninsula at Pusan (VR), Taiwan at Keelung (VR); possibly South China Sea along the Chinese coast and off Hong Kong (VR, dubious); Coral Sea (VR); Philippines (Palawan, Mindanao) and Bonin Island (VR). Australia: Queensland (F-O), entire coastline to NSW and South Australia (CA; F), Tasmania (F-O), Great Australian Bight (CA; F), Western Australia (CA; F-O). New Zealand, both North and South Islands (CA; O), particularly Dunedin, Otago peninsula and environs on South Island (F-O). Stewart Island, Chatham Islands (O); Campbell Island, recent attack there upon a diver (I-R?). New Caledonia (VR).

Literature: Nakano and Nakaya (1987); Uchida et al. (1996); Bruce (1992); Last and Stevens (1994); Francis (1996); Ayling and Cox (1982); Cappo (1988).

Central Pacific:- Hawaiian Islands off Oahu, Hawaii and Northwestern Islands (R); Marshall Islands at Bikini (VR); Easter Island, based on recent shark attack.

Literature: Taylor (1985; 1993); G. Burgess (pers. comm.).

Northeast Pacific:- Gulf of Alaska (VR), British Columbia, Washington State (R), Oregon Coasts (O), abundance increases southwards to Northern California (CA; F), Central California (CA; F, particularly from Sonoma County, Marin Co., the Gulf of the Farallones, Año Nuevo Island, Santa Cruz, Monterey Peninsula to the Big Sur); Southern California and Channel Islands (CA; F-O), Baha and offshore at Isla de Guadalupe (O). Sea of Cortez (I-R), Mexico (R) to Panama (R).

Literature: Klimley (1985); Royce (1963); Pike (1962); Fitch (1949); Kenyon (1958); Follet (1966); LeMier (1951); Kato (1965); Bonham (1942).

Southeast Pacific:- From Panama south through Ecuador and Peru to Chile; data sketchy, however, for range north of Chile. Northern and Central Chile (CA; O) to Archipelago de los Chonos (45úS), possibly more southerly to Cape Horn.

Literature: Engaña and McCosker (1987)

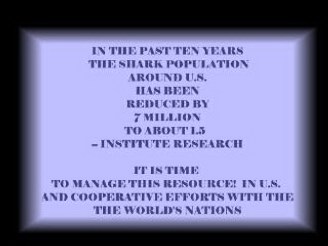

• Abundance

Overall population estimates for this species are unknown and even regional or localised estimates are sketchy. Inter-annual abundance of these sharks can be very variable and unpredictable, giving rise to 'good' and 'bad' years, in a colloquial sense, for great white numbers, albeit that the causal factors are essentially unknown. Off the eastern USA, National Marine Fisheries Service statistics from 1965 to 1983 show a decline in ratio from 1:67 to 1:210 . Other indices of catch-rates are available from: a) California, between 1960-85 as 0 to 14 sharks per year (mean 3.2; Klimley, 1985); b) Natal, between 1974-88 as 22-61 sharks per year (; c) Central Mediterranean Sea (Sicilian Channel), between 1950-94 as 0-8 sharks per year (mean 2.2, author, unpublished data). In other areas such as Brazil and Hawaii, captures are much more nominal and sporadic over time.

• Movements and Nomadicy

Occurrences are known within a wide sea-surface temperature (SST) range of ca. 7.0 to 26ûC, but the species seems most frequently encountered in temperate waters between 13 to 20ûC. Patterns in movement and abundance within some areas (e.g., the seasonal position of the 15ûC isortherm in the Northwest Atlantic [Casey and Pratt, 1985]) appear linked with seasonal variations in sea surface temperature, as warmer waters influx poleward towards the northern limit of regional white shark distribution. However, temperature may have only a limited effect on the distribution of these sharks. An anomaly in white shark distribution, at least on face-value, is their absence (or extreme scarcity) within temperate coastal waters of Atlantic Europe - despite suitable habitats and prey (including seals) being available to them.

Tracking of white sharks by telemetry has afforded an insight into facets of their spatial behaviour, both in the horizontal and vertical sense. An efficient, graceful cruiser at slow speeds (averaging 3.2km/h over a distance of 190km, in a classic experiment off New York by the late Frank Carey et al., 1982), the white shark, in keeping with other lamnids, maintains elevated temperatures within the swimming muscles, brain, eyes and gut to at least 13.7ûC above the surrounding sea temperature - an adaption which may provide an increase in neural, digestive and muscle activity and function. The species is also capable of short-duration, high-velocity pursuits, even launching entirely clear from the surface in spectacular repeated leaps. 'Blind' traditional telemetry and more recent remote videography using parasitic 'Crittercam' video cameras reveals that white shark predominantly cruises in a purposeful manner, either just off the bottom or near to the surface, but spending very little time at midwater depths unless stimulated by baits (Strong et al., 1992; Goldman et al., 1996; Greg Marshall, pers. comm.).

This species is freely capable of making long-distance movements on localised, regional and intercontinental scales. Although information is rather limited by the essential rarity of these animals, some data on movements has been afforded through tag-and-release programmes in America, South Africa and Australia. For example, two white sharks tagged by a joint Cousteau Society and South Australian Department of Fisheries (SADF) Team near Dangerous Reef were later recaptured some 220km to the east, near Antechamber Bay on Kangaroo Island. Similarly, a South African specimen was found to have travelled approximately 780km in just 28 days. But whilst tagging has demonstrated these rather long-distance movements, the same studies have also highlighted an interesting propensity for white sharks to exhibit a high degree of localised, temporary residency. At the Farallon Islands, a stark archipelago some 40km due west of San Francisco, researchers have identified a number of individual adult white sharks through distinctive body-markings and fin abnormalities - rather as accomplished in equatable studies of whales and dolphins. Over the course of successive yearly field studies on the island since the early 1970's, it has been shown quite conclusively that some of the Farallon sharks return to the locale annually in the Autumnal months, often arriving and departing on virtually the same repeated days or weeks with surprising homogeneity. White sharks are scarce at the islands between January and September, but precisely where those seen in Autumn move away to through the remainder of the year is presently unknown. Comparable recent work at Dyer Island, South Africa and Dangerous Reef has yielded similar results to the Californian study - some tagged (and thus readily identifiable) sharks returning repeatedly to the same places, where they are then resighted by observers with considerable frequency. Nevertheless, an even greater proportion of tagged sharks are never resighted again - testimony to the nomadic side of these fish.

It is clear that voyages by white sharks can cover great distances. Although primarily occupying and journeying within continental and insular shelf habitats, some white sharks - and generally individuals from the larger size classes - undertake long-distance journeys across the great ocean basins. They have been found, albeit sporadically, both in mid-Atlantic at the Azores archipelago and mid-Pacific at the Hawaiian Islands. Nominal captures have also been reported from other discrete oceanic locales - including Gough Island in the South Atlantic and Bikini Atoll in the Pacific's Marshall Islands, as well as rather more captures from pelagic gillnetting operations for squid in the epipelagic zone of the North Pacific. There is no evidence to suggest that these treks have some reproductive significance and the occurrence of white sharks at any one of these localities is very variable in terms of both numbers, seasonality and bias of gender. Taylor (1985, 1994) suggested that white sharks may frequent Hawaiian waters through some predatory interrelationship with humpback whale calving cycles. A similar hypothesis of a relationship between white sharks and sperm whales may be applied to explicate occurrences at the Azores, although in both cases this is very tentative. It is equally likely that the phenomenon simply manifests the opportunistic, nomadic behaviour of some larger white sharks - a trait that may conceivably increase with older individuals that can readily subsist on large oceanic bony fishes, cetaceans and other sharks. Whatever the case, these records demonstrate that despite the wide geographic separation between known centers of abundance, the white shark's distribution cannot be considered as disjunct. For example, inter-hemispherical movement between temperate areas, whereby white sharks traverse very warm equatorial zones, is plausible. A possible mechanism is tropical submergence, where the shark descends into and travels within deeper, cool oceanic waters across the equatorial zone. However, white sharks also occur in shallow inshore and offshore waters in the tropics and may may not need to use this mechanism unlike some epipelagic and deep-water sharks.

There appears to be complimentary sides: the nomadic, 'just passing through' style of spatial behaviour and the more systematic pattern of repetitive occurrence, as demonstrated at select sites such as the Spencer Gulf, the Farallons, and the Dyer Island Channel by tagging and field observation. Clearly, the populaces of these 'classic' white shark localities are in a state of continual flux, with numbers of sharks on any one day comprising both 'resident' individuals and short-term nomadic visitors, and with all of them moving around and seldom staying close to observers. It is suspected that some white sharks occupy and patrol a favoured home range in the broad sense of the word (particularly some large individuals at Farallons), and that a proportion of attacks on divers are actually an aggressive if limited response to the invasion of this 'personal space'. The issue of white shark spatial behaviour is an enigmatic topic, whose secrets may ultimately be revealed through current advances in electronic tagging, data-logging tags, seabed-monitor arrays and long-distance satellite telemetry.

|

Predatory Biology

Social and Complex behaviour

Contrary to the lonely JAWS spectre of an idiot eating-machine, the white shark is actually a social animal, exhibiting a raft of complex behaviours. Intraspecific ethology and sociobiology in this species are now receiving dedicated research attention, and are considerably more complex than previously recognised or embodied within the archetypal 'lone killer' image. Field-observations have described pecking-orders at feeding aggregations at carcasses which seem based upon a size-hierarchy (see Pratt et al., 1982), where larger sharks dominate in eating; this has also been seen off South Africa with floating baits, but is complicated by individual motivation. Some of the great white's swimming-modes are interpreted as ensuring avoidance of conspecifics and maintenance of a personal space, such as cautiously-timed 'turn-aways' between two animals converging on reciprocal approaching courses. Similarly, the 'parallel-swim' mode is often seen, whereby two sharks heading on the same vector retain an unfluctuating distance from each other, again as what seems to be maintenance of personal space . What appears to be a non-injurious means of deflecting competition whilst feeding at the surface has been observed off California and South Africa, whereby white sharks strike or splash conspecifics with the caudal fin in a spectacular exhibition dubbed 'tail-slapping' (Klimley et al., 1996). White sharks will also shove or 'body-slam' other white sharks by lateral movements of their bodies, and also use their caudal fins to strike boats and even observers aboard them .

Many white sharks, both adult and immature, have slash and puncture wounds of superficial nature to the head and dorsum, which are inflicted by the teeth of rivals during brief bouts of intraspecific aggression and competition, especially near food resources but very likely also through courtship or other social interactions. In the past, these marks were almost exclusively explained as being caused by the flipper nails or teeth of pinniped prey, but closer inspection and further observation in the field largely excludes this theory. Aggression between these sharks is very inhibited, considering the potential for severe wounding or worse, and includes rather cursory bashing, slashing and grab-release biting with both the upper and lower-jaw teeth. Where elicited on inanimate items offered to white sharks, much of this casual mouthing seems to be investigative rather than any attempt to ingest, and the observer is left with an overwhelming image of the shark using its fearsome jaws with very fine control for tactile sense and manipulation as well as for actual feeding (authors, personal obs.). By the same token, such rather low-intensity biting is typical in attacks on humans, with puncture marks, as opposed to actual flesh removal, being commonplace. Whilst white shark attacks are often explained through a process of 'mistaken identity' with natural prey, underwater observations suggest that the sharks readily distinguish between humans and prey-animals such as pinnipeds. A more compelling hypothesis is that many such 'hit and run' interactions are motivated by interspecific aggression; perceived invasion of personal space, or other motives not directly allied to feeding such as 'play'. As white sharks apparently interact socially by low-intensity biting and grabbing, at least some oral contact with humans and other animals that are not regular prey may have a social framework, with sharks behaving with humans as they would with other sharks. Humans in such interactions may not understand what the shark's body language (including displays such as gaping and hunching) may signify (if they notice them at all) and what responses are appropriate to the context, until the shark proceeds further in the interaction and grabs the person. Work in progress off South Africa suggests that white sharks as individuals and groups confronted by free-swimming skin and SCUBA divers are usually not aggressive even when baits and chum-trails are present but may investigate the divers quite closely without showing any signs of perturbed, agonistic behavior.

White sharks attracted in baited situations exhibit curious behaviours, such as inverted surface-swimming with the mouth agape and gape-displays on the approach to shark cages, divers and so-on, at least some of it being thwart-induced or displacement behaviour, in a generic sense, as well as int. This activity that is not unlike that observed with the shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus. It may appear simply maniacal on films, but such ethology must have a more deep-rooted purpose. In the gape-displays, the palatoquadrate (upper jaw) is exposed for a protracted period during non-feeding, rather akin to a dog snarling and bearing its canine teeth. Indeed, its purpose may be exactly that of the dog - an agonistic threat display that warns-off competitors or intruders of personal space with a display of natural weaponry that requires little further explanation! Some white sharks couple this type of behaviour to a unnaturally stiff swimming mode, with pectoral fins held markedly downwards, and back slightly arched ('hunch' display) and accompanied by periodic gaping that may be directed both intraspecifically (to other white sharks) and interspecifically (for example, to people - but quite possibly, or probably, also to seals, dolphins and other animals). The conspicuous dark axillar blotch (highlighted by bare white axillar skin around it), which is only normally exposed by the 'pecs-down' hunching style of swimming, may play a visual, communicative part in this posturing. Notably, it is a feature of pigmentation found on both white sharks and the shortfin mako (but not the porbeagle or salmon shark) - suggesting that its role, if any, is duplicated or at least overlapping in both species. It's occasional absence as a feature on Mediterranean white sharks may be evidence of a low population density, with very limited intraspecific contact; i.e., the feature has been progressively lost in an adaptorial, evolutionary sense. However, white sharks without axillary spots also occur off South Africa and California where white shark numbers are greater and social contact injuries are commonly seen on sharks. Whilst this explanation remains totally speculative, the apparently low degree of contact between Mediterranean great whites other than for reproduction is further indicated by the dearth of scratches, stabs and other allied marks as seen on the heads and anterior parts of these sharks in regions elsewhere (see above).

Great white shark

Carcharodon carcharias (Linnaeus, 1758).

Conservation of the great white shark

Threats

• Directed Fisheries

In directed terms, white sharks are primarily exploited for the curio trade, with jaws and individual teeth fetching high prices on both local and international markets. Often associated with these commercial ventures are sportfisheries, as formerly undetaken in a high-profile manner off Southern Australia, South Africa, and to a lesser degree in other regions such as the eastern USA. Whilst a number of white sharks are taken annually by rod-and-line charter-boats, a further, more unscrupulous method employed by some operators involves passive-fishing by means of large baited meathooks secured to anchored oil-drum floats by heavy-gauge chains. These 'chain-line' and associated 'big hook' fisheries are generally unstructured, unregulated or downright illegal; their aim being solely the procurement of white shark jaws or teeth for trade. Individual dentition removed from smaller white sharks may sell for a higher price in aggregate than complete sets of small jaws, and the threat posed by the curio-trade encompasses white sharks across the entire size and maturity-range. This trade is not restricted to jaws and teeth; even entire specimens, some attaining in excess of 5 metres, have been preserved by freezing or taxidermy for static public display or as private trophies and curios.

In some areas, the excellent, palatable flesh of this species, rich in red muscle when properly filleted, can fetch high retail prices for human consumption and considerably more than that of other similarly-exploited sharks such as the shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus. However, coupled equally to consumer disquiet over the 'maneater' tag, and the fact that white shark meat is not uncommonly high in mercury, commercial use for human cuisine is geographically and culturally patchy. Because very few specimens marketed by fisheries are listed under species-specific landings statistics, consequently the precise level of such exploitation remains poorly documented.

Some rod-and-line sports fisheries have operated both on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America, but rarely are these directed solely at white sharks. In the Mid-Atlantic Bight, juveniles are occasionally landed in angling tournaments - some 140 specimens were taken in those waters between 1971 and 1991, by tournaments and research vessels . In the past, big-game charters were run with some success to target adult specimens in the same area. One operator, Frank Mundus of Montauk, Long Island, was particularly active in this regard and his association with catching big white sharks inspired the 'Quint' character in Peter Benchley's JAWS. More opportunistic ventures, such as the harpooning of sharks feeding on whale carcasses, was not unknown in the waters off Long Island. The National Marine Fisheries Service now seeks to control and outlaw targeted captures of white sharks in the northwest US Atlantic (now supported by legislation enforced since early 1997) and has successfully encouraged and coordinated the tagging and releasing of these and other species of sharks for many years.

On the US Pacific coast, white sharks have been targeted in the past off both central and southern California, albeit with variable success. White sharks were a popular but somewhat elusive quarry for anglers in Southern Californian waters. Their activities were frequently inspired by the large cash rewards offered at the time by oceanariums, who sought great whites for public display as a cash-in on the 'Jaws-mania' of the era. Juvenile sharks were often taken very close inshore and larger specimens fell victim to harpoon-wielding hunters. More recently, one-off opportunistic ventures were undertaken to capture white sharks at the Farallon Islands near San Francisco, a National Marine Sanctuary reknowned internationally as a white shark locality. The virtually simultaneous capture of four sharks at the islands in 1984 was met with dismay by the scientific establishment and some sectors of the public and media. Fishing-forays to the islands or elsewhere in Californian waters in search of white sharks have been outlawed by State Legislation SB-144.

• Indirect Mortality and Beach Meshing

The propensity for white sharks to scavenge from commercial longline and net fisheries makes them very vulnerable to accidental entrapment. Worldwide, specimens are reported annually from gill-nets, trammels, herring-weirs, purse-seines, tuna-enclosures and hooked upon surface and bottom longlines and set-lines.

Somewhat more directed pressure is manifested in the form of anti-shark beach netting, installed to ensure the safety of bathers at selected localities. Shark nets have been installed at some Australian beach resorts in New South Wales since 1937, and along Queensland's Gold Coast since 1962. Similar measures are taken in South Africa where in 1952, responding to a series of high-profile local shark attacks, the first nets were installed off Durban. This was followed by the installation of two further nets at Amanzimtoti in August 1962. As of 1990, 14% of the 326 km of Natal coastline between Mzamba and Richard's Bay was protected by 44.4 km of gillnets (Dudley and Cliff, 1993), with the operation controlled by the Natal Sharks Board.

In the Queensland Shark Control Programme and NSW meshing operation, there is data to indicate an irregular decline in white shark captures over the past three decades. The Natal net-catches - a total of 591 white sharks between 1974 and 1988, with from 22 to 61 examples caught annually (Cliff et al., 1989) - indicates a similar but less clearly-defined downward trend. Conscious of mounting environmental concern and criticism, there is an increasing willingness by meshing contractors to tag and release sharks found alive in the nets, although mortality remains high overall both to sharks and other inoffensive marine creatures including rays, guitarfish, dolphins and turtles. The broad effect of these meshing programmes on marine ecology - not least because they are totally unselective by its very nature - has created considerable controversy and some current research is directed at developing harmless alternative measures, such as electronic barriers to repel sharks.

• Habitat Loss or Degradation

Being a highly mobile, pelagic species the threat of habitat loss may appear generally minimal to white sharks. However, disruption of prey availability poses potential threats and in at least one area - the north Adriatic Sea - white shark captures and sightings have declined markedly in the latter half of this century, possibly through depletion of teleost prey stocks, dolphins and possibly monk seals. All of these factors may themselves be the effects of increased pollutants, overfishing or both. Despite this, white sharks are adaptable predators capable of shifting diet as conditions dictate and may simply cease inhabiting a degraded area and move elsewhere. As tagging studies have demonstrated, these sharks can display a varying degbeen so in the recent past, also serve as preferred feeding habitats.

"Yachtsman's Guide to the Bahamas! & Yachtsman's Guide to the Virgin Islands... finest authoritative

resources for all cruising these Caribbean regions!"-- KWR ...Updated and published annually since 1950 with the

endorsement and sponsorship of the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Nearly 500 pages chocked full of useful island

boating information including detailed tips on how to cross the Gulf Stream, where to stay, and what to do. Includes

sketch charts, aerial and ground photographs, and detailed information... Key West Register's affiliate the

Bahamas Institute always has these two books down below in the chart room on the 'Joan Marie' during the

recent research expeditions as well as the "Cruising Guide to the Florida Keys, 12th edition" which is also a 'Must Have!'

Key West Register has not found better guides for those cruising or those just wanting wonderful reading! Click icons

"Later - See You On Duval Street"©

Press releases contain statements of a forward-looking nature relating to future events or future financial results. Investors are cautioned that

such statements are only predictions and actual events or results may differ materially. In evaluating such statements, investors should specifically

consider various factors, which could cause actual events or results to differ materially from those indicated from such forward-looking statements.

The Company undertakes no obligation to publicly release the results of any revisions to these forward-looking statements that may be made to reflect

events or circumstances after the date hereofor to refledt the occurrence of unanticipated events.

The Name sharkfest .com™ Trademark owned by Key West Register Corp.

used for research projects since 1939 and as part of the advisory partner of the Key West Institute

|

Key West Institute researchers based in Abaco Cays/Bahamas and Grand Bahama

Key West Institute researchers based in Abaco Cays/Bahamas and Grand Bahama